In Conversation: 80Hz

Can you speak about the relationship between internal and external sound, such as the surrounding traffic, nature, rain etc.?

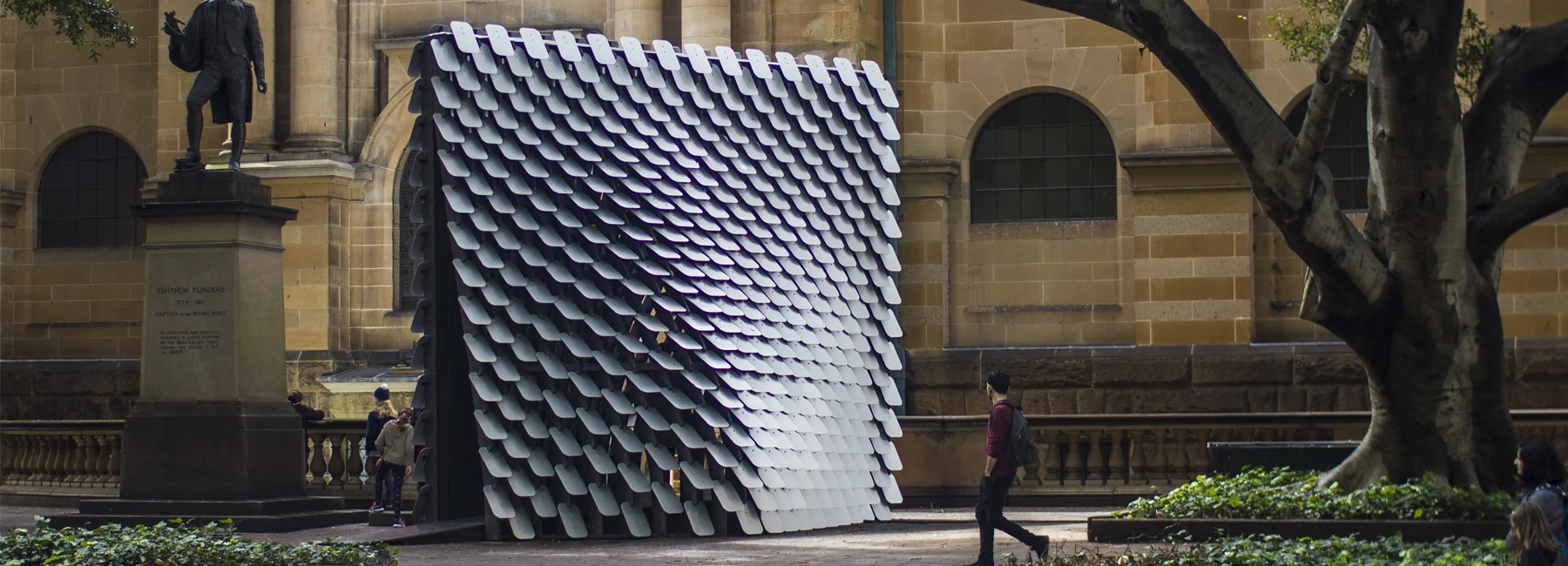

I have always been fascinated by the idea of putting sounds in a space, and this is the first outdoor project I’ve done so I was interested to hear how the soundscapes would blend with the noise of the city. Practically there are some constraints in terms of what will cut through the city drone but it’s just an external constraint that you have to work with. We didn’t really see it as a limitation. Sound is free flowing, you can’t put it in a frame or behind a glass case, it permeates it’s environment, fully saturating every space it occupies. I quite liked the fact that whatever we created would inevitably be entwined with the sounds of the city and I think that ads an unexpected aspect to the experience. One of my favourite moments during process was listening to the soundscapes in the structure while it was raining, you could hear every drop of rain hitting the aluminium shingles and even though you’re in the middle of the city it felt as if you where in a little sound bubble that no one else could hear.

Can you explain the process behind assigning the visual metadata to its audio counterparts?

We worked in a program called Max which allows you to work with data in a number of ways. We had to start by building a musical framework for the data to be filtered into. The first thing we did was to constrain the notes to a given musical scale, then we assigned chords to different colours in the painting based on the dominant and accent colour. We needed some form of structure for the composition so we scanned the painting at set intervals to give us a rhythmic sequence of colour and therefore chords. When a face is detected in the painting the melody generator weights it’s note choice to more musical intervals based on the current chord that is playing. Some other data sets like intensity and complexity inform chord voicing with more complex(no. of distinct colours detected) and rich painting having more open and spread out chords while less complex and more intense paintings having tighter and more closely voiced chords. The rest of the data went into informing instrument choice for each of the different stems in the composition; Piano, Melody, Pads and Bass as well as the arrangement of these stems.

How long did it take you to write the program?

The program itself didn’t take that long to write once we had a clear idea of how it would work. We sat on the concept for quite a while, Wes Chew and Luke Mynott supervised the sound aspect of the project and there is a wealth of knowledge between them, they also both have very musical backgrounds which was helpful. There was a period of about 3 weeks where we just let the idea percolate in the back of our minds and we’d pass each other in the hall every so often and say ‘hey what if it worked like this’ or ‘could we try build it like this?’ It was quite nebulous for a while, but once the concept clicked the program came together in about 2 weeks.

Did any of the compositions that took form surprise you?

I definitely have my favourites! One thing that did surprise us initially was how nice they sounded, too nice actually. It sounded like a human had composed some pretty music to accompany the paintings, which makes sense in a way because the compositions just followed our musical rules and never ‘broke’ those rules the way a human would. So we had to break it, a little. We started to look at the interaction between the metadata and how we could infuse an element of randomness into the composition.

Can you visually anticipate how a painting will be interpreted by the program?

To a certain extent yes, but the way that all the metadata comes together gives you a lot of variety. For example you could be looking at two landscape painting with quite broad brush strokes and not a lot of contrast between the colours and if you knew the program you could anticipate that the chords are going to change quite slowly and make quite small leaps in pitch up or down but when you overlap metadata like artistic period, dominant colour and artwork size the differences start to compound.

Do you feel as though the soundscape for each painting offers an accurate audio interpretation of the corresponding visual form and structure?

I’m not sure anyone has come up with a completely accurately way to interpret paintings as soundscapes, certainly not musical ones. This is just our take on it. A reimagining of a collection of paintings from the State Libraries archives in a data-driven audio experiment. We didn’t want it to be too abstract, we wanted to capture people imagination and I think music is a great way to do that.

Many of the compositions are piano based, with a multilayered approach to intertwining rhythm, percussion and chord progressions against an almost exploristic and journey-like traversal of its visual counterpart. How did you decide which sound elements would be assigned to which set of visual data?

It was all about looking for patterns, obviously we didn’t want all of the pieces to sound the same and the element that seemed to give us the most distinction between compositions was instrument choice and tempo, so we assigned those elements to datasets that had the most variation between paintings. Metadata that was more binary or had very little variation between paintings was assigned to more subtle elements of the composition like chord voicing.

As the crank turns, we enter a continuous loop of sound and composition. Human interaction clearly plays a fundamental role here. Is it possible for a new composition to emerge every day, depending on where the lever sits and how it transitions through the 40 paintings?

Interaction is a big part of the experience and we hoped that the visitors would feel apart of the creation process. We also wanted it to be fun, it’s right in the city, there are no pristine white walls or barriers or staff watching to make sure you do the right thing, it’s exploratory in nature so we wanted to reward people for their curiosity. The lever manipulates the audio in different ways depending on the where in the reel you are. The program is designed to create smooth transitions between images but if you zoom in on those transitions there is space for some unexpected audio moments based on the semi-random way the program distorts the compositions. Thomas had said fairly early on that he wanted people to feel as if they where the DJ and I think that comes back to the idea of fun, when you see a kids face light up when they make the connection that what they are doing is affecting the sounds that they are hearing, that’s a really special moment.

How were you hoping people would react, and how have people surprised you?

I wasn’t sure how people would react. I hoped that exhibiting these paintings in a new light would help people make their own connections to some of the images. Each painting tells a portion and is a part of Sydney’s story, and I think that the way we re-contextualise our own history to make it relevant for ourselves is really important. People are always looking for cues on how to interpret the world around us, and a lot of the people I’ve seen interact with the painting have said things like ‘this one sounds sad because the picture is sad’ or ‘ this one is dark because the painting is dark’ but in reality none of those things factor into our compositions, I think without guidance people just see what they are predisposed to seeing.

The compositions seem to paint a picture through melody and dissonance. Do you feel as though the paintings have developed a new personality due to a new layer of sound?

Yes absolutely, it’s hard to do anything without adding another complex layer of meaning to the life of an artwork. Music is a really powerful tool for establishing connection, it ties into so many memories and emotions that are deeply personal to each individual.

How has the dialogue between sound, image and architectural form influenced the way you respond to each painting?

Wow, I don’t know. It’s more of a feeling for me. I think that by putting it on the street with a beautiful structure that you can explore and touch and feel and lick (would not recommend) if you wanted to and having a musical soundscape to accompany it that you can interact with and control makes the paintings feel a bit more accessible. I love walking around a gallery and observing incredible classical art but there always feels like a bit of a disconnect, like it’s not meant for me. I come from an on demand, media soaked, avo toast, remix culture generation and this artwork doesn’t try to relate to you or hit you over the head with some sort of message, it’s just there ready to be explored if you wanted to.

Are there any composers you are influenced by, or anyone you were trying to emulate when originally mapping out the program?

Thomas had a really great list of references that included Aphex Twin, Nils Frahm and Ryuichi Sakamoto. I got really excited by this because those could have come straight from a list of artists I have on heavy rotation. I think that you can hear a bit of that influence come though in the compositions. It was pretty clear that the compositions would need to be very piano centric, with the span of time we where trying to represent it made sense to choose an instrument that has remained relevant for the last 300 years.

How did Thomas approach you and explain his idea? Do you feel as though the finished project has turned out as you expected, or has it flourished into something entirely new?

I think the original intention is there, I know for Thomas the project has had quite a life cycle. When Thomas came to Sonar Sound with the idea I’m pretty sure the project was already a few incarnations deep. I didn’t expect it to have quite so much personality and I think a lot of that comes down to the work we put into the play between humanised, random and rule based composition.

You have almost sculpted the sound like an audio architect, creating a musical landscape which offers a totally immersive and interactive experience. Which paintings and compositions stand out most to you, and why?

I quite like the portraits; I think there is something quite beautiful about trying to imagine their story and the addition of the compositions just fuel my imagination. One in particular is the painting of the Maori warrior, there is something almost spiritual about that painting and I think that the accompanying composition captures something of that essence, for me at least.

How did the architectural installation itself come together, and how does it work to compliment the experience for an interactive audience?

It was amazing to see it come together, I remember seeing Thomas putting together odd shapes in some sort of bunker below the State Library, it was great. Then it came together on the street it all made sense. There is no signage on the street and most people are very hesitant to go anywhere if they don’t know they are allowed to so the structure itself needed to be enticing. On top of that people are generally quite self-conscious so the fact that there are no staff members supervising the artworks as well as the privacy you get from the structure itself creates a safe environment to explore and just be a bit of a kid again.

Interviewer: Anthea Mentzalis